Key Takeaways

- Hypoglycemia means low blood sugar—typically when blood sugar drops below 70 mg/dL

- Hypoglycemia is extremely rare for non-diabetics who don’t take insulin

- Low blood sugar alerts from your CGM generally should not cause concern

The following is intended to be general information and does not constitute medical advice. Please consult your physician if you have questions or concerns.

Glucose, or sugar, is your body’s main source of energy. Hypoglycemia means low blood sugar, or when the glucose in your blood drops below 70 milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL). Some people will have a different range of normal (ie. a lower normal range). For people who are not on diabetic medicines like insulin, sustained hypoglycemia is extremely rare!

You might see it while undergoing intense exercise, or as a big dip after a large spike (like after your Oral Glucose Tolerance Test). But your body knows to react and ramp up your glucose production to get back to a safe range.

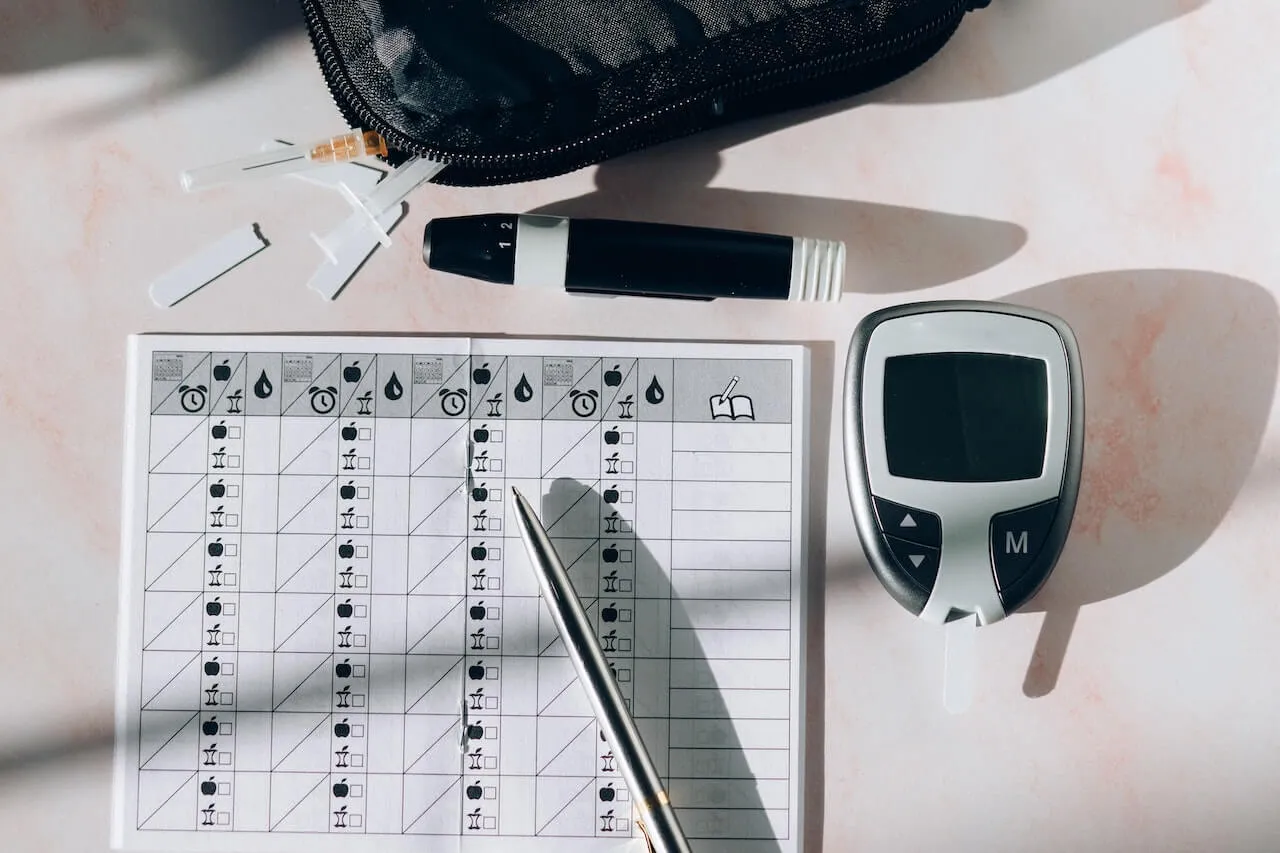

As a reminder, the CGM is measuring interstitial glucose, which might be a little different from your blood glucose, and can be lower or higher depending on what else is happening with your body. The CGM measurement can lag behind a fingerprick blood glucose measurement for a short amount of time because it takes a sample from your interstitial fluid. The trends and information you get from a CGM provide an accurate picture of how you respond to different foods and exercise.

<p class="pro-tip">Also Read: The Scientific Evidence for Using CGMs for Weight Loss</p>

These are average glucose ranges:

- 72–99 mg/dL when fasting

- 80-110 mg/dL before a meal

- Less than 140 mg/dL 1–2 hours after eating

True hypoglycemia is defined<sup>1</sup> by:

- low blood glucose (less than 70 mg/dL, but again, there is a range)

- symptoms that can be attributed to low blood glucose (see the table of symptoms below)

- the symptoms go away when your blood glucose improves.

Most people may not experience any symptoms when they dip. If your glucose drops below normal, you may experience the symptoms listed below.

{{mid-cta}}

Hypoglycemia Symptoms

Source: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

Severe hypoglycemia happens when your blood glucose drops so low that you’re unable to do anything for yourself and you should seek treatment right away. This severe condition is most common in people who need to take insulin or other medications to lower their blood sugar.

I got a low blood sugar alert from my CGM. Should I be worried?

Generally, no! Your body is an expert at self-regulation and has mechanisms built in to bring your glucose back up to a safe range. You may see low blood sugar alerts if:

- You worked out and had a glucose drop or spike and following dip. You shouldn’t experience any symptoms during this process- your body will make glucose to help fuel your muscles. Some people will have a glucose spike just from working out if it is sufficiently rigorous!

- Your CGM is still calibrating. When you place a new sensor, it typically takes 24–48 hours for the CGM to normalize.

If you don’t have any symptoms and your glucose reads on the lower side, you don’t need to eat sugary food to bring it back up.

If you do have mild symptoms like shakiness, or sweatiness, sit down and relax. Consider eating something small. If you continue to have these symptoms with a normal range or have more concerning symptoms, consider seeking medical care.

If I get low blood sugar alerts, does this mean that I could be diabetic?

The dangerous levels of hypoglycemia that you hear about are usually in response to diabetic medicines that are intended to lower glucose. It is very rare for people to have persistent hypoglycemia in the absence of these medications, bariatric surgeries, or other rare conditions. Diabetes is defined by persistently high levels of blood glucose, not low.

Is it common for people who haven’t been diagnosed with diabetes to experience hypoglycemia?

No, it is not common. Remember, true hypoglycemia requires that you have both low blood glucose and hypoglycemia symptoms that resolve (go away) when your glucose goes back up.

CGMs measure interstitial glucose, which is correlated, but not always exactly the same as your blood glucose. So if your reading is a little low but you feel fine, generally that is not something to worry about!

What are the causes of hypoglycemia?

Hypoglycemia can happen from a variety of causes. One of the most common causes of true hypoglycemia is accidental low blood sugar from medications meant to treat diabetes like insulin or sulfonylureas. People who have had bariatric surgeries can also experience hypoglycemia events.

Other causes of hypoglycemia include critical illness, malnutrition, and a variety of rare conditions like insulin-secreting tumors and adrenal insufficiency (when your adrenal glands do not produce enough steroids like cortisol).

All of these are serious conditions and anyone with them should be under the direct care of a medical provider.

Most commonly, people think low blood sugar results from not eating enough or from burning a lot of fuel during a long cardio workout. Being “hangry” does not usually mean you are at a dangerously low level of blood glucose.

If I’m trying to lose weight, won’t I burn more fat when my glucose is low (and how low is safe)?

This is a complicated question! Daily fluctuations in glucose are a normal part of life, and the human body is always regulating to stay within a safe range.

Weight loss generally happens as a result of a negative energy balance, when your body expends more energy than you eat. This takes into account basal metabolic rate and effects of the type of food you eat and the physical activity you do.

Keeping your glucose in a stable range can be a good goal because it reminds you to avoid energy-rich foods that are high in glucose and fat. An increase in physical activity also helps keep your glucose in a stable range.

Glucose also triggers the release of insulin and, for some people, decreasing your insulin levels increases the time you spend burning fat. This can lead to weight loss.

But, it’s possible to keep glucose stable and not lose weight. This depends on what you eat and other lifestyle factors (such as stress, sleep, etc.). For example: eating butter, bacon, and lots of oil all day won’t spike your glucose, but these foods have a lot of non-nutritious calories! Compared to an apple or other fruit and plain yogurt, the latter may give you a little glucose spike but can be better for you in the long run.

What is hyperglycemia and how is it different from hypoglycemia?

Hyperglycemia means high blood sugar—much as hyperactive means a high level of activity. Hyperglycemia is much more common than hypoglycemia.

For short periods, this is a normal physiological process in response to some foods and physiologic or psychological stress.

If you eat an apple and your glucose goes up a bit, that’s fine! This doesn’t mean an apple is unhealthy.

Sustained or very high hyperglycemia is a symptom of diabetes; work with your doctor to monitor your glucose if you see consistently high readings that deviate often from the average ranges referenced above.

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)